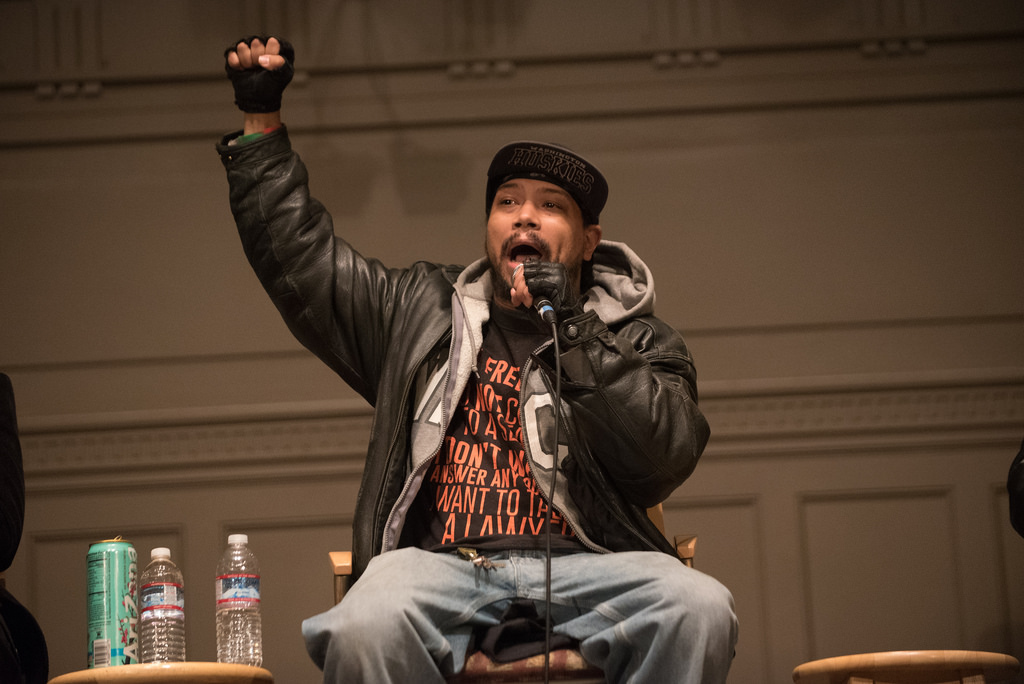

Michael Renaissance is our Co-Director of Campaigns, and our newest staff collective member.

Q: What was your first visceral awareness of the scope of the climate crisis?

A: It’s difficult for me to identify a specific moment when I was like: this right here is wrong and we must do something to change it…because there isn’t one. My awareness evolved.

When I was in elementary school and I was introduced to “global warming” and the whole reduce, reuse, recycle campaign, I was immediately filled with passion to make a difference. That faded when I was faced with life-or-death peril and my immediate concerns supplanted the protracted concerns for the planet. I never lost that passion, but many years were devoted to surviving the interlocking systems of oppression that make up our society.

Then the dystopian science fiction, documentaries, and books that I absorbed during my teens and twenties reinforced my understanding of the ecological precipice our civilization is on. When I finally made it to college during my late twenties, I was introduced to the true meanings of injustice, oppression, and intersectionality—and how they often existed along the lines of race, class, gender, and place of birth. Environmental racism and genocide assumed precedence as a focal concern for me after that.

The concerns I had as a child regarding the garbage on the ground in our neighborhood seemed trivial when I began to understand that the cheap places my family could afford to live in were affordable because of how toxic and unhealthy the areas were. Yet, because I grew up poor and had never been out of the country, issues like the Amazon rainforest disappearing may as well have been on another planet — they were of little concern to me. Until the connection was made for me, that to folx in the Global South I am the one percent, and as such that I am partly responsible for the oppression they suffer. Even as poor and as harmed as I grew up in the United States, I was still privileged enough to be born inside the feudal privilege walls.

Q: Tell us a little about your path to activism.

A: I sobered up in 2001, when I was nineteen, then I went to a Job Corps facility, and quite by accident, I joined the student government. The next term I became the president of the school. I thought that working in government was the way to effect change. In fact, I wanted to be the president of the United States, and started pursuing a law degree to achieve that aim. When I made it back to college in 2011 at North Seattle College (NSC), I became the treasurer of the school and made a lot of good changes. This was during the major recession and at the end of the Occupy Movement. In between NSC and starting at the University of Washington (UW) in 2013, I went to my first protest, the Portland Rising Tide event that was protesting coal trains and we shut down the Columbia River for a day.

At that moment, I realized there was another way to display power, utilizing the protections of the first amendment, and that a critical mass of people was more vital to change than any government office. A little later, I went to Greece while studying international justice (and planning to be president!), and learned about the negative impacts against immigrants from the African continent to the European Union. My experiences there were a rude awakening.

And yet: two days before I left to work on those global injustices, Michael Brown was executed by police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri…and the reality that injustice surrounded me at home sunk in. I hoped, as many did, that the indictment would hold, but on the night that the decision to let him go was made, I hit the streets with everyone else and never left. I was also studying the school to prison pipeline, mass incarceration, and police brutality as part of my history degree—and studying the rise and fall of civilizations and social justice movements throughout the world. I knew that I wanted to be in the movement, and I believed the movement needed me so, in the movement I remained. I have been fighting the system and building community power ever since.

Q: What’s most personal to you about the climate crisis?

A: This has changed throughout my life, and will continue to do so. Currently, the thing that most motivates me to work on addressing climate change is that at my core I hold the value of wanting to focus 25% on deconstruction and 75% on building. I am focused on building in a world that will sustain the victories we win as a people concerned with social justice. My nieces and nephews will be living in the world we leave for them, and their children’s children’s children will wonder why we did or didn’t do the things to overcome the climate crisis; this is always on my mind. The Seven Generations principle that comes from the Iroquois Confederation. What is most personal to me is my moral compass and my commitment to leave the world better than it was left for me.

Q: Do you have a particular appetite for any targets we’re not currently working on, or strategies we’re not using (or not using as powerfully as we could)?

A: I come from a deep background in collective community-driven organizing. I have spent the majority of the last several years organizing around police brutality and to end mass incarceration with Black Lives Matter and the Mass Liberation Project. So, for me, it is not as much a matter of what we focus on, but rather how we focus on it. I would like 350 Seattle to begin hosting community conversations, especially with members of the communities who are the most impacted by the negative effects of climate change so that we can begin to form an agenda that directly responds to the concerns of our community and reflects their/our interests. This will not only help us to pull away from the implicit paternalism within our organizing structure/strategy, but it will also help to strengthen our movement and encourage more people to participate as we fight for the issues they care most about. It also begins to create the kind of processes that can sustain a healthy world once we win.

Q: If you could wave a wand and have one major climate policy implemented or decision made in the region, overnight, what would it be?

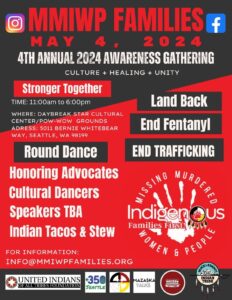

A: In the Pacific Northwest, and in particular on the occupied ancestral lands of Coast Salish Peoples, I’d make it so that politicians would implement the plans and policies that frontline and Indigenous communities put forward. The people most impacted should be the ones making the decisions about those impacts — and the elected politicians should be doing what they were elected to do, which is to work for us.

Q: What do you find difficult about this work? Most joyful?

A: The hardest part of any kind of organizing is managing relationships.

More often than not, when we discuss relationships we are referring to our close organizing comrades, our constituency, and our base. There are implicit and explicit expectations that must be honored, which often come with traditions and rituals that vary between communities. Sometimes we tend not to account for the trauma that motivates many people to engage in the movement. This means that our organizing must allow space to heal. We also need to be cautious that the manner in which we hold our labor of love does not create new trauma and instead limits harm as we live our way into a new way of being in relationship with one another.

There are also the relationships we hold with those who stand in opposition to what we believe, how we feel, and what we know. They’re also human, and deserve respect no matter how much we disagree with them, or how much they have harmed or will harm us. This is difficult for me, as it is for most people. There was an Indigenous lesson that was taught to me many years ago that has become part of my modus operandi: “The greatest warrior will end a war before it ever begins.”

Warriors obviously fight when they must, but fighting should be a last resort. In fighting, many of our communities are defending ourselves, and I do not think they are wrong to do so. However, if there is a way to respect and honor the humanity of even the people we might consider enemies in our struggle to survive and to create a sustainable way of living on the only planet we have, together…then that is what I believe we should do. This is difficult, but it is the labor of love that is necessary for us to achieve our aims. When the war is over we will have to live with one another, so the less repair work we have to do, the better.

If that is how much love we must share with those who are in opposition to us, then how much more should we be sharing with those who are on our side or on the fence? These are the daily struggles I contend with as I organize with so many amazing people.

Q: What helps to sustain you when you’re feeling overwhelmed or burnt out?

A: When I feel like burn-out is settling in, there are two primary directions my mind and body tend to travel. One is reflexive, while the other is intentional. The reflexive and rather unhealthy answer is that I continue to plow through my labor of love, becoming more reactive and aggressive, less communicative, more abrasive, less strategic, and ultimately harmful to the people around me. The more intentional, but ultimately still unhealthy direction is that I often disengage from the labor of love by separating from society and urban situations escaping into the wilderness to meditate and take photos. The latter is merely a bandage to a much larger problem that has, when left unaddressed, led into the former direction I reflexively take. I have gone through burn-out on multiple occasions.

Over time, I have developed a practice of meditation, consultation, exercise, and rest that I maintain as a continual practice to prevent burn-out. The two most important elements of my current strategy are sleep and meditation. I’ve found that while organizing, sleep is often easy to sacrifice—but the amount of sleep I get is directly proportional to my level of serenity, my ability to think rationally, and my ability to focus without becoming overwhelmed. My daily practice of meditation allows me to ground my spiritual essence in my truth and the truth of others; that we are all human beings deserving of love and healing. My practice of meditation helps me slow down enough for me to prioritize the tasks before me and to understand why they fit into the order I put them in. This frees up the brain space I would otherwise devote to thinking that there is not enough time and that nothing is ever finished. It helps to quell the negative internal dialogue that if left unchecked is a symptom of the two unhealthy directions I mentioned above.

My primary objective is not to enter into burn-out at all. If I recognize its onset, then I scale back and recalibrate myself by reinforcing my practices. When I am holding this practice well for myself, it also helps me to make or respect the space that others need for themselves.

Q: We know that where people live (urban or rural, apartment or house) shapes not only their lives, but their climate impact. What’s your ideal living situation, if practicality is no concern?

A: I have lived in the city most of my life, and not been well-off. In fact, most of my life I have been quite poor. I never really felt at home anywhere, but there was always a place that I felt the safest, which is the structure I called home and where my family was located. We did not make it out of the city much growing up, but during the few times that we did, I was introduced to places that I felt more at peace. As I grew older, mostly as an adult, the woods and the ocean call to me the most. An ideal situation would probably be a minimalist intentional community with relatively little electricity, that relies primarily on subsistence within a watershed that includes hunting, foraging, and farming. Gven the work we do and how much we rely on technology to maintain the quality of work and relationships, a place with lots of woods, natural water, a small community, a large garden, and internet would be ideal.

Q: Anything else you’d like to share with us?

A: Naw, that’s a lot. But if you have questions you may always ask.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and conciseness.